An Arduino frequency counter by WA5BDU

Introduction

This is going to be a fairly long description of the frequency counter and the ICs and circuits that make it go. That’s for people who might want to roll their own or modify this one. Otherwise, if you’re mainly interested in building one, gloss over all those details and just focus on the schematic diagram and source code.

A few years ago I wanted to design and program a frequency counter that could be embedded in a transceiver and output the frequency in Morse. I’d mostly moved from the PIC to the Arduino but I learned that the Arduino’s ATMega family of AVR microcontrollers could not perform high speed frequency counting directly like the PIC can. The PIC12F683 that I used has a prescaler front end that runs independently of its internal clock and can capture counts at over 100 MHz and as high as 140 MHz in my experience. It’s described in my blog linked below:

http://wa5bdu.blogspot.com/2017/11/pic-frequency-counter-with-morse-output.html

While doing my homework for that project, I got a suggestion from one ham that I try the 74LV8154 32‑bit counter as a front end for an Arduino. It looked interesting so I took note.

My current need or at least my desire, was to design another frequency counter that could output readings at regular intervals to a serial port so they could be captured in a .CSV or other data array format and plotted. This was to plot drift and detect sudden jumps in frequency in the VFO of an old boatanchor I’ve been working on.

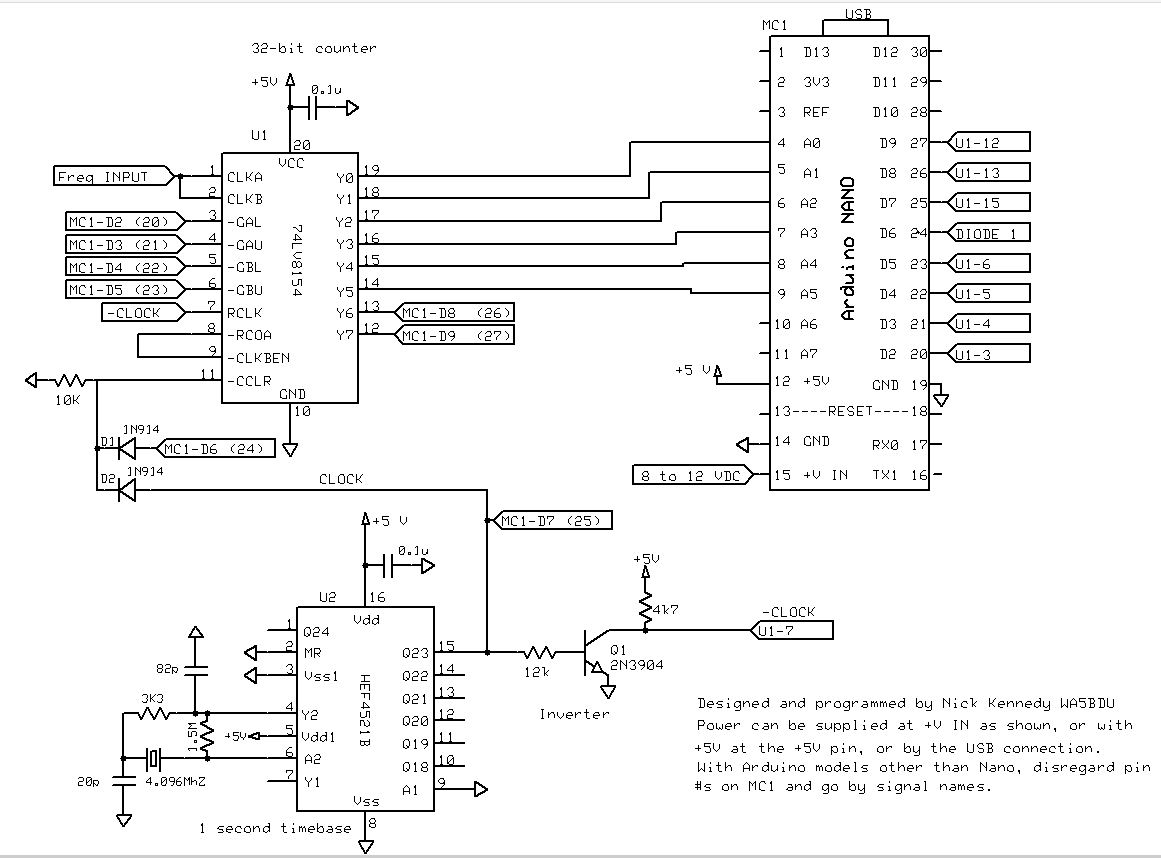

The 74LV8154 32-bit counter

This is a great chip for this purpose. It has a 32 bit counter so it can go to 4.29E9 before rolling over. The 32 bit number is read from four registers using 8 dedicated pins. Selection of which of the four registers to put on the pins is made using four dedicated pins, GAL, GAU, GBL, GBU, meaning A-lower, A-upper, B-lower, B-upper. (The counter can be divided into two 16-bit counters ‘A’ and ‘B’ but here we use them as one big 32-bit counter.)

Counting proceeds when –CCLR is HIGH and stops with counts cleared to zero when it is LOW. So the task is to make –CCLR HIGH for a precise amount of time (about 1 second in this case) and read the count at the end.

The internal count is transferred to the four output registers by a high to low transition on the RCLK pin. Timing of this action is important as we’ll see.

For the 32-bit counter, pins 1 (CLKA) and 2 (CLKB) are tied together and the signal to be counted is connected there. The chip is being operated at 5 VDC supply voltage, so the input signal should be approximately at the TTL level.

The data sheet doesn’t give the maximum frequency in direct terms, but I’m counting 50.125 MHz on it.

The HEF4521B, 24 stage divider with crystal oscillator

This is the chip that generates the approximately 1 second timebase signal. I actually made a version at first that didn’t use an external crystal timebase but instead let the Arduino generate it with a timer interrupt. It worked pretty well but had about 5 to 10 Hz of wobble in the last digit when measuring a 7 MHz signal. I wanted to get better stability.

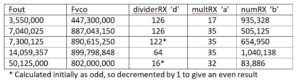

I considered using a 32,768 Hz crystal such as are used in clocks and watches, but I didn’t think that could give the stability I wanted. I chose a 4.096 MHz crystal from my parts bin. It’s not an exact power of 2, so I don’t get an exact 1 second timebase but that’s fine as the actual value is accommodated in software. I need a 0.5 Hz signal to give the 1 second high time. The Q23 output on pin 15 does that, since 2^23 is 8,388,608. This gives me a 0.48828 Hz output with a period of 2.048 seconds and a high time of 1.024 second.

The data sheet gives component values for 50 kHz and 500 kHz crystals. I wasn’t sure if it could go to 4 MHz and did have difficulty until I noticed that in addition to Vdd and Vss pins, there are also Vdd1 and Vss1 pins that need power. No power, no oscillation. I stuck with the recommended values for resistors and capacitors except for making the the series resistor 3k3 Ω instead of 47 kΩ recommended for 500 kHz.

Not much else to say about this chip. It gives a lot of flexibility for your choice of crystal by having outputs for Q18 through Q24.

Logic and putting it together

The basic idea is pretty simple. Connect the 1 second timebase clock to –CCLR so the chip will do a ~1 second count while it is high, then transfer the count to the output registers and read them into the Arduino, assemble and do arithmetic, essentially dividing the number of counts by the time of the timebase to give frequency.

There are a couple of complications, naturally. I’d like the end of the counting period to activate RCLK which will transfer the count to the registers. But this takes a low to high transition and at the end of the counting period, the clock is going from high to low. I hoped to avoid adding any more ICs to do miscellaneous functions, no NAND, NOR or inverter packages if possible. So I used a single transistor as an inverter, which you see in the schematic. Its output is –CLOCK or “NOT CLOCK”, being 180 degrees out of phase from CLOCK and it is used to trigger RCLK.

The next complication is with the signal to –CCLR. It goes low at the end of the counting period, which triggers RCLK, but it also clears the count in the same instant. So I have a potential timing race: Will RCLK cause the count to be latched to the registers before the simultaneous –CCLR clears it to zero? I don’t know the answer, but I didn’t want to leave it to chance.

To deal with this, I have the Arduino delay the low signal to –CCLR with one of its I/O lines. But I don’t want any software latency at the other end, where –CCLR is taken high, so I want the signal to be “armed” before that transition arrives. That’s the function of the two diodes, which I guess you’d call a negative logic AND gate. Both signals must be low for a low level to reach –CCCR.

The Arduino also needs to know when to enable and when to block the clear signal. So another I/O line monitors the clock signal. There’s plenty of time during each half cycle for it to do its thing. During the positive half, it raises the output signal to block the clear. After the signal has gone low, -CLOCK has triggered RCLK and the output signal can be take low to clear the count and allow the CLOCK signal to start counting at the transition to high.

I hope that all made sense.

The single IC version

In this version the HEF4521B and associated components plus the inverter are omitted and the clock and latch signals are provided by the Arduino. I’m posting a separate source code for this version since it works well enough to be useful and simplifies the hardware. Arduino I/O line D6 goes to the RCLK pin and line D7 goes to –CCLR.

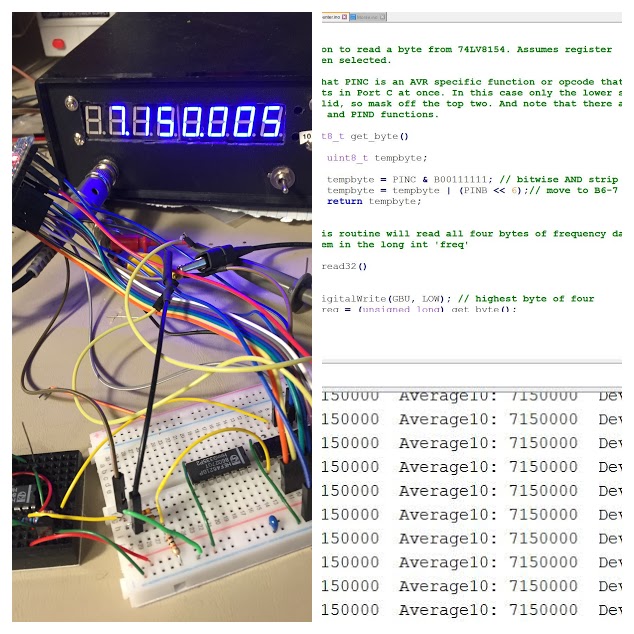

Displaying the output

Since my original intent was to capture data over time for plotting, I’m printing the frequency to the serial port on one second intervals. Note that on the Arduino, you can turn on a serial monitor by pressing Control-Shift-M and see this output. On the version without the crystal timebase I was trying to quantify the amount of ‘jitter’ I get from software uncertainties. I wanted the deviation from average, not from some absolute value, so I keep a running average of the last ten counts and display each reading’s deviation from that average. Here it is now looking at a 50.125 MHz signal:

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

frequency: 50124948 Average10: 50124948 Deviation: 0

So this is pretty solid. Usually there’s at least a bobble in the Hertz digit.

Here’s an output taken for the version with timing taken from the Arduino, looking at a 7.150 MHz signal:

frequency: 7149968 Average10: 7149966 Deviation: 6

frequency: 7149965 Average10: 7149967 Deviation: 1

frequency: 7149967 Average10: 7149967 Deviation: -2

frequency: 7149965 Average10: 7149967 Deviation: 0

frequency: 7149972 Average10: 7149966 Deviation: -1

frequency: 7149968 Average10: 7149967 Deviation: 5

I presume that at 50 MHz the deviations would have been about seven times as great. So … this was not bad but the addition of the crystal timebase was worthwhile.

Other incomplete things:

I: Other output options

An LCD or other display independent of a PC or serial monitor would be an obvious addition to consider.

I think my first move in this direction would be to add output in Morse, like the AFA (Audible Frequency Annunciation) type output of my PIC counter. I’d want a pushbutton to tell the Arduino when to speak up. I’m close to having this working.

II: Other time base and calibration options

The one second time base is good as it gets you 1 Hz resolution. But a 0.1 second measurement would be good too as it would update ten times as fast. Since I’m dealing with powers of two, I’ll probably go with a 1/8 second measurement. Then I just multiply my counts by eight and process as usual.

Also, wasting one second for every second spent measuring isn’t good. I’m sure there’s going to be a way to reset and restart the time base so that the time between measurement periods is kept to a minimum.

As for calibration, right now my method is pretty crude. I measure a known frequency with no correction, then take a ratio of the reading to the actual frequency and use that to correct the measuerement. It works, but having to revise my source code if things change isn’t good. I haven’t yet tried a trimmer on the crystal to see if I can tweak it in. Doing the software thing once and then tweaking a trimmer thereafter would be a good approach.

Also though, my adjustment math in software requires me to use floating point math. The numbers are just too big even for unsigned long integer math. But floating point limits the resolution to something above one part in 1E7. A good solution would be to have a crystal that will divide down to exactly 1 second, with a trimmer. Then I could avoid the software math corrections entirely. Update: I’ve got some 4.194304 MHz crystals on order that should do the job.

IV: Input signal conditioning and amplifying.

Currently I’m using the counter with input signals of at least a couple of volts p-p at the input. Some sort of amplifier plus limiter/squarer is normally used to increase sensitivity. The one from my PIC counter made from a single NAND gate gave me sensitivity in the range of 35 mVpp to 180 mVpp. Take one section of a 74HC00 NAND gate package. With one gate, tie the inputs together and feed them through a 0.1 uF capacitor. Connect a 22 k-ohm resistor from output to input. This is a simple solution that works great.

Link to source code for version with the crystal time base:

http://www.wa5bdu.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Freq_counter_xtal.ino

Link to source code for a simpler version where the Arduino provides the time base:

http://www.wa5bdu.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Freq_counter.ino

Link to the schematic diagram:

http://www.wa5bdu.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Schematic-snip-frequency-counter-1.jpg